The federal regulatory framework for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) regulation in the United States (U.S.) is rapidly advancing, with administrative action to further investigate and govern PFAS coming from regulatory programs that have not previously regulated PFAS, as well as from recently introduced legislative bills in Congress. In continuation of Trihydro’s PFAS article series, we build upon the information presented in Part 1: Existing Rules by discussing pending and potential near-future PFAS regulations, as shown in the “EPA Actions” column of Figure 1 below. Due to the rapid pace and frequency of PFAS developments, future installments will cover additional federal and state regulatory developments that have been introduced since this article was published.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is advancing PFAS regulatory actions under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), Clean Water Act (CWA), Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), and Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). The April 27, 2021 memorandum from EPA’s Michael Regan introduced the “PFAS 2021-2025 – Safeguarding America’s Water, Air, and Land” strategy and confirmed EPA’s resolve to make PFAS a priority by moving forward with multifaceted PFAS actions, including regulations.

Figure 1: Federal PFAS Regulations Overview

127d1ddd27eb62c49ea3ff0000e20177.jpg?sfvrsn=ca967f6e_0&MaxWidth=900&MaxHeight=&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=A2AFE625FCB43C1043DB68EE377C45FAD931FC50)

Are Any Pending Federal PFAS Regulatory Actions Relevant to My Company?

Companies that discharge stormwater or wastewater into national waterways, manufacture or apply pesticides, have facilities near bodies of water, have waste disposal sites, synthesize or import chemical substances, or have corrective action sites already subject to regulation under the CERCLA or RCRA may be affected by the PFAS regulatory actions. PFAS are also present in many materials that could affect sites that are not impacted by other (non-PFAS) chemicals. Trihydro’s PFAS experts are available to assist companies in understanding the extent to which PFAS regulations may apply to their site(s).

Emerging and Anticipated Federal PFAS Regulatory Actions

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA)

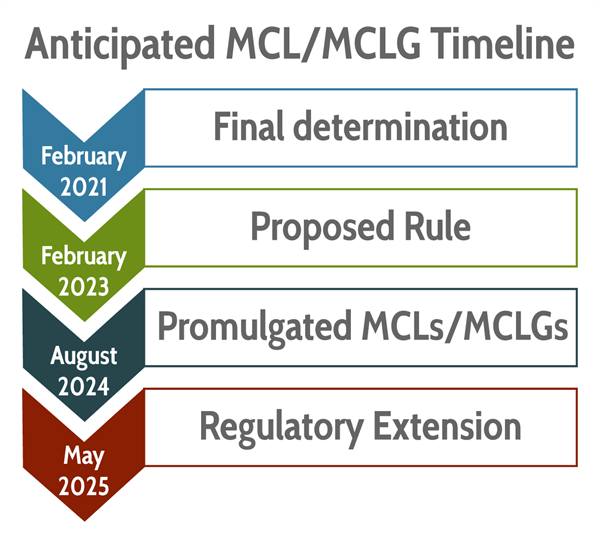

Regulatory actions concerning PFAS in drinking water date back to 2009, with EPA issuing non-enforceable Provisional Health Advisory values for perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). Fast forward to July 2021, and EPA is well underway to establish the enforceable drinking water maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) and non-enforceable maximum contaminant level goals (MCLGs) for PFOS and PFOA. The MCL/MCLG pathway within the National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) has already advanced through the fourth Contaminant Candidate List (CCL 4) regulatory determination. CCL 4 prioritizes contaminants of national concern, confirms actual/potential health risks, and ensures that analytical methods as well as sufficient data exist to support the NPDWR development. The CCL 4 regulatory determination was finalized on February 22, 2021, thereby initiating the proposed rulemaking pipeline with draft MCLs/MCLGs for PFOS and PFOA expected in two years. Following the statutory time frame, PFOS/PFOA drinking water standards could be promulgated as early as August 2024. However, delays are expected due to the arduous legislative process required, combined with the need to balance health impacts, water testing requirements, cost of compliance, and limited treatment options available to the stakeholders impacted by new drinking water standards.

Figure 2: Anticipated MCL/MCLG Timeline

In concert with the MCL development, EPA has regularly monitored public drinking water supplies for existing contaminants and, beginning in 2001, for select new contaminants. These substances are subject to the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR), with 6 PFAS compounds appearing in 2012 (UCMR 3) and expanding to 29 in the proposed Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5). The 2021 UCMR 5 would require public water systems (PWS) to monitor for the expanded set of PFAS compounds from 2023 through 2025. The analytical procedures are to include the drinking water methods EPA 533 (for 25 PFAS compounds) and EPA 537.1 (for the remaining 4 compounds).

SWDA Analysis:

The expansion of the number of PFAS compounds included in the UCMR 5 underscores rapid advances in analytical methodologies and indicates EPA’s intent to quantify potential public exposures to an increasingly broader range of PFAS compounds. Moreover, EPA’s recent actions related to the SDWA indicate that drinking water standards for PFOS/PFOA are forthcoming and likely to include additional PFAS compounds (such as the recently evaluated perfluorobutane sulfonic acid [PFBS]), for future monitoring, risk assessment/management, and regulation.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) is another organization that may provide insight into upcoming regulatory changes. The ATSDR recently finalized the toxicological profile for PFAS, including the minimal risk levels (MRLs) that were originally proposed in 2018. The 2021 MRLs for PFOS and PFOA are considerably more conservative (i.e., lower) than the corresponding EPA’s reference doses. Because EPA has often followed public health recommendations introduced by ATSDR, there is a possibility that EPA will follow ATSDR’s example by adjusting PFOS and PFOA reference doses for the purpose of MCL/MCLG derivation, which would result in more conservative (lower) MCLs/MCLGs.

Clean Water Act (CWA)

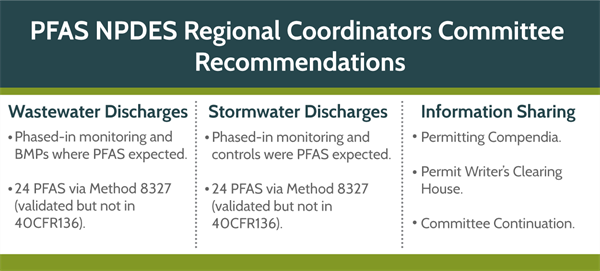

The CWA, among other aspects, focuses on point sources of pollutant discharges. Specifically, the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) monitors and regulates constituents entering national waterways. Recently, the NPDES program was subject to discussions by the NPDES Regional Coordinators Committee (Committee), which issued a set of recommendations regarding NPDES permits and discharges potentially containing PFAS due to the use, storage, and release of these chemicals at permitted facilities. The interim strategy for EPA permit writers follows the general rule for “pollutants otherwise expected to be present” and includes monitoring via the analytical method EPA 8327 for non-potable water. Although this method has not been promulgated in 40 CFR 136, the permitting authority can specify it as a suitable method. The Committee further recommended the implementation of best management practices (BMPs) and stormwater discharge controls. The implementation of information sharing, including permitting compendia, Permit Writers’ Clearinghouse, and a continuation of the Committee were advocated as well. Additionally, if there are any state-issued NPDES permits containing PFAS elements, writers are advised to consult those permits to ensure alignment and consistency.

Figure 3: PFAS NPDES Regional Coordinators Committee Recommendations

Continuing the focus on point source releases, the March 17, 2021 Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (March 2021 ANPRM) explores the scope of available data to support potential future rulemaking for effluents, pretreatment, and New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) related to the Organic Chemicals, Plastics, and Synthetic Fibers (OCPSF) categorical discharge criteria. According to EPA, this category is linked to manufacturers and formulators whose effluents are most likely to contain PFAS. Currently, the Effluent Limitations Guidelines (ELGs) for OCPSF do not include PFAS. To develop effluent regulations, EPA is seeking public comments via the March 2021 ANPRM on a number of issues, but particularly on identities of PFAS compounds, wastewater streams, treatment, pollution prevention, disposal practices, and analytical monitoring methods for effluents.

CWA Analysis:

Given the early stage of the concept of explicitly incorporating PFAS into the NPDES permits, as well as the Committee’s recommendation to include PFAS only if they are expected in point sources as a result of facility’s PFAS operations, it is unlikely that many NPDES permits will be immediately impacted, other than perhaps those for OCPSF facilities that handle PFAS. However, as state and federal programs continue to develop regulations, making the PFAS status as a pollutant commonplace, it would not be unexpected to see PFAS included in future NPDES permits.

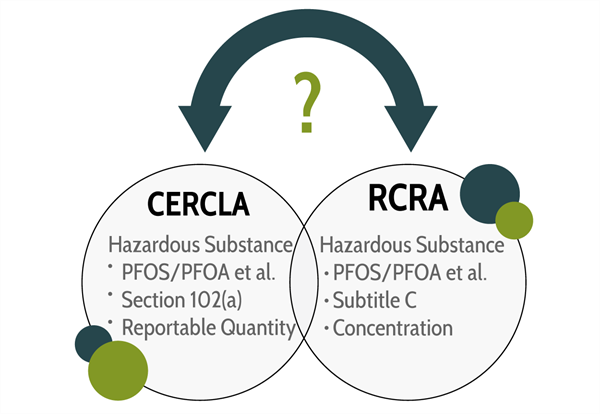

CERCLA Superfund/RCRA Waste

Another PFAS initiative within EPA involves the potential mechanisms to implement the hazardous designation of PFAS (specifically PFOS/PFOA). As of January 2021, EPA issued an ANPRM (January 2021 ANPRM) and invited input from the public regarding the application of existing authorities under CERCLA, RCRA, or CWA to regulate PFOS/PFOA. In their prospective regulatory impact assessment, EPA identified several entities likely impacted by the hazardous designation should it fall under CERCLA:

- Manufacturers and processors of PFOS/PFOA

- Manufacturers of products containing PFOS/PFOA

- Downstream product manufacturers and users of PFOS/PFOA products

- Waste management facilities

- Effluent treatment facilities

Within the above categories, specific industries may include:

- Aviation

- Carpet manufacturers

- Car washes

- Electroplaters

- Paint and coatings manufacturers

- Fire-fighting foam manufacturers

- Landfills

- Fire departments/training centers

- Paper mills

- Petroleum refineries and terminals

- Photographic film manufacturers

- Wax and cleaning product manufacturers

- Polymer manufacturers

- Textile mills

- Wastewater treatment plants

While EPA has not provided a specific timeline for proceeding with the hazardous designation, the January 2021 ANPRM provides insights into the agency’s thinking. Namely, EPA requests feedback on the additional 23 PFAS compounds found at the National Priority List (NPL) sites, PFOS/PFOA precursors, reportable quantities, individual vs. class of substances regulation, threshold of hazardous concentrations in waste, analytical determinations for waste classification, and any new waste listing categories. The type of information requested suggests a considerable level of detail and breadth of EPA’s PFAS CERCLA/RCRA considerations, which are likely to continue as this important aspect plays out.

Figure 4: EPA's Options for the Hazardous Designation of PFAS

In the meantime, EPA has recommended groundwater PFOS/PFOA screening levels of 40 parts per trillion (ppt) to determine if further investigation is necessary at contaminated sites, and 70 ppt (following EPA’s Lifetime Drinking Water Health Advisory) as a preliminary remediation goal (PRG) for contaminated groundwater that may be a source of drinking water in the absence of sufficient state, tribal, or applicable or relevant and appropriate requirements (ARARs). However, certain states have adopted significantly lower concentration standards (e.g., Michigan has adopted a groundwater standard of 8 ppt for PFOA and 16 ppt for PFOS).

To further support contaminated site work and the appropriate management of PFAS waste, EPA has released interim guidance on destroying and disposing of certain PFAS and PFAS-containing materials that are not consumer products, such as aqueous film forming foams (AFFF). The interim disposal guidance focuses on three primary options: incineration, landfilling, and deep well injection. Each option has advantages and shortcomings, and none are ultimately recommended for PFAS disposal at this time. Research needs for each are documented in the interim guidance.

CERCLA Superfund/RCRA Waste Analysis:

Since CERCLA and RCRA are the two major US laws governing contaminated sites and toxic wastes, hazardous designation of PFOS/PFOA (and perhaps additional PFAS later on) will have momentous impacts on a wide range of industries. Moreover, work at contaminated sites will be affected, with some NPL and RCRA corrective action sites potentially subject to reopening.

Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA)

On June 28, 2021, EPA issued a proposed rule on PFAS reporting and recordkeeping under TSCA Section 8(a)7 for manufacturers and importers, with the anticipated compliance period retroactive to January 1, 2011. This represents a new TSCA reporting requirement, and although similar to the existing quadrennial Chemical Data Reporting (CDR), there are differences. The rule is to exclude processors and low volume quantities (i.e., less than 10,000 kilograms per year), but not byproducts, articles with PFAS, or small businesses. As with any other TSCA submittals, the reporting standard is “known or reasonably ascertainable” and the information obtained is used to sustain the protection of human health and the environment. The number of compounds fitting EPA’s TSCA definition/chemical structure for PFAS and subject to TSCA reporting under the proposed rule is estimated at 1,364. This count is well in excess of what is estimated for PFAS on the current TSCA Inventory. To avoid duplicative information requests, EPA indicates that certain data elements will be coordinated among the reporting programs. Approximately 12 months will be allotted for the reporting parties to prepare and submit the one-time Section 8(a)7 data via a reporting tool in the Central Data Exchange (CDX) system. A total of 22 separate data elements will be required, ranging from PFAS identity to volumes released into water, air, and land. EPA is requesting comments from the public by August 27, 2021 (EPA-HQ-OPPT-2020-0549).

On a related note, subsequent to the 2020 Significant New Use Rule (SNUR) concerning long-chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (LCPFACs) in surface coatings, carpets, textiles, furniture, electronics, and household appliances, EPA issued a corresponding compliance guide. However, that document was withdrawn in June 2021 by the new administration citing insufficient handling of public comments, as well as narrowing of the scope and strength of the 2020 SNUR. The rule language was unimpacted by this action and, presumably, a replacement guide will be provided.

TSCA Analysis:

Of all the environmental rules, TSCA is the most advanced in terms of encompassing PFAS. From new substance notifications to reporting, TSCA is EPA’s primary workhorse in terms of amalgamating existing information and requesting new data for new chemicals. The proposed rule fits into that model and future TSCA reporting requirements could be reasonably anticipated. If finalized, the Section 8(a)7 reporting rule will add to the existing reporting burden associated with reporting and recordkeeping compliance.

Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA)

EPA is investigating the source of PFAS contamination in a mosquito control pesticide product. Studies conducted in December 2020 on fluorinated high-density polyethylene (HDPE) containers in which the contaminated pesticides were packaged implicated the HDPE packaging as a PFAS contamination source. EPA has indicated that PFAS is not a known/registered active or inactive ingredient, nor is it otherwise an intentional pesticide additive. Rather, the functional application of PFAS is to improve container specifications for stability, permeation, and breakdown. EPA testing revealed the containers’ fluorocoating included up to 8 PFAS species (including PFOA) in concentrations ranging from 20 to 50 parts per billion (ppb). The distribution and use of the impacted mosquito control product have since been terminated, but the general use and application of fluorinated HDPE containers continue. At this time, FIFRA regulations neither require nor explicitly prohibit storage container fluorination.

FIFRA Analysis:

Given the continued use of fluorinated containers, possible due diligence may include an inquiry with the product manufacturer regarding this issue. If the container is suspected of containing PFAS, a best course of action may be to discontinue the product use as its application may lead to PFAS in the treated areas.

Looking Ahead

To gain insight into where federal regulations may be heading, the proposed house bill “PFAS Action Act of 2021,” lays a comprehensive legislation plan that seeks to accelerate PFAS prevention and clean-up activities. In part, the PFAS Action Act would:

- Amend the SWDA to require EPA to establish a national drinking water standard for PFOS and PFOA within 2 years of enactment.

- Designate PFOS/PFOA as hazardous substances under CERCLA within 1 year of enactment and require EPA to determine whether to list other PFAS within 5 years.

- Amend TSCA to specify that comprehensive toxicity testing shall be conducted on PFAS.

- Designate PFOS/PFOA as hazardous air pollutants within 180 days and require EPA to determine whether to list other PFAS within 5 years.

- Require EPA to place wastewater limitations and pretreatment standards for the introduction or discharge of covered PFAS within 4 years of enactment.

- Establish a PFAS infrastructure grant program within 180 days of enactment to assist community water systems affected by PFAS.

- Prohibit unsafe incineration of PFAS wastes and place a moratorium on the introduction of new PFAS into commerce.

- Create a label for PFAS-free products within 1 year of enactment.

- Require EPA to provide guidance on minimizing the use of firefighting foams and other PFAS containing materials used by emergency responders within 1 year of enactment.

In terms of occupational exposure, the proposed senate bill Protecting Firefighters from Adverse Substances (PFAS) Act introduced on February 4, 2021, directs the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to develop guidance for emergency personnel on PFAS protection for themselves and the environment. Specific rule objectives included:

- Develop and publish guidance for firefighters and other emergency response personnel on training, education programs, and best practices to: (a) reduce and eliminate exposure to PFAS from firefighting foam and personal protective equipment, and (b) prevent the release of PFAS from firefighting foam into the environment.

- Develop and issue guidance for firefighters and other emergency response personnel on foams and non-foam alternatives, personal protective equipment, and other firefighting tools and equipment that do not contain PFAS.

- Create an online public repository, which shall be updated on a regular basis, on tools and best practices for firefighters and other emergency response personnel to reduce, limit, and prevent the release of and exposure to PFAS.

In conclusion, the ramping up of multifaceted regulatory actions by EPA across various existing regulatory programs is leading the regulated community closer to specific PFAS rules and regulations, especially concerning water, contaminated sites, wastewater, and solid waste. As such, close surveillance of regulatory developments concerning PFAS should be part of regular compliance due diligence.

Want to learn more?

Trihydro’s subject matter experts regularly present on and analyze the latest PFAS developments and are available to discuss how PFAS regulatory updates affect your company’s reporting obligations, compliance, permitting, and overall operations.